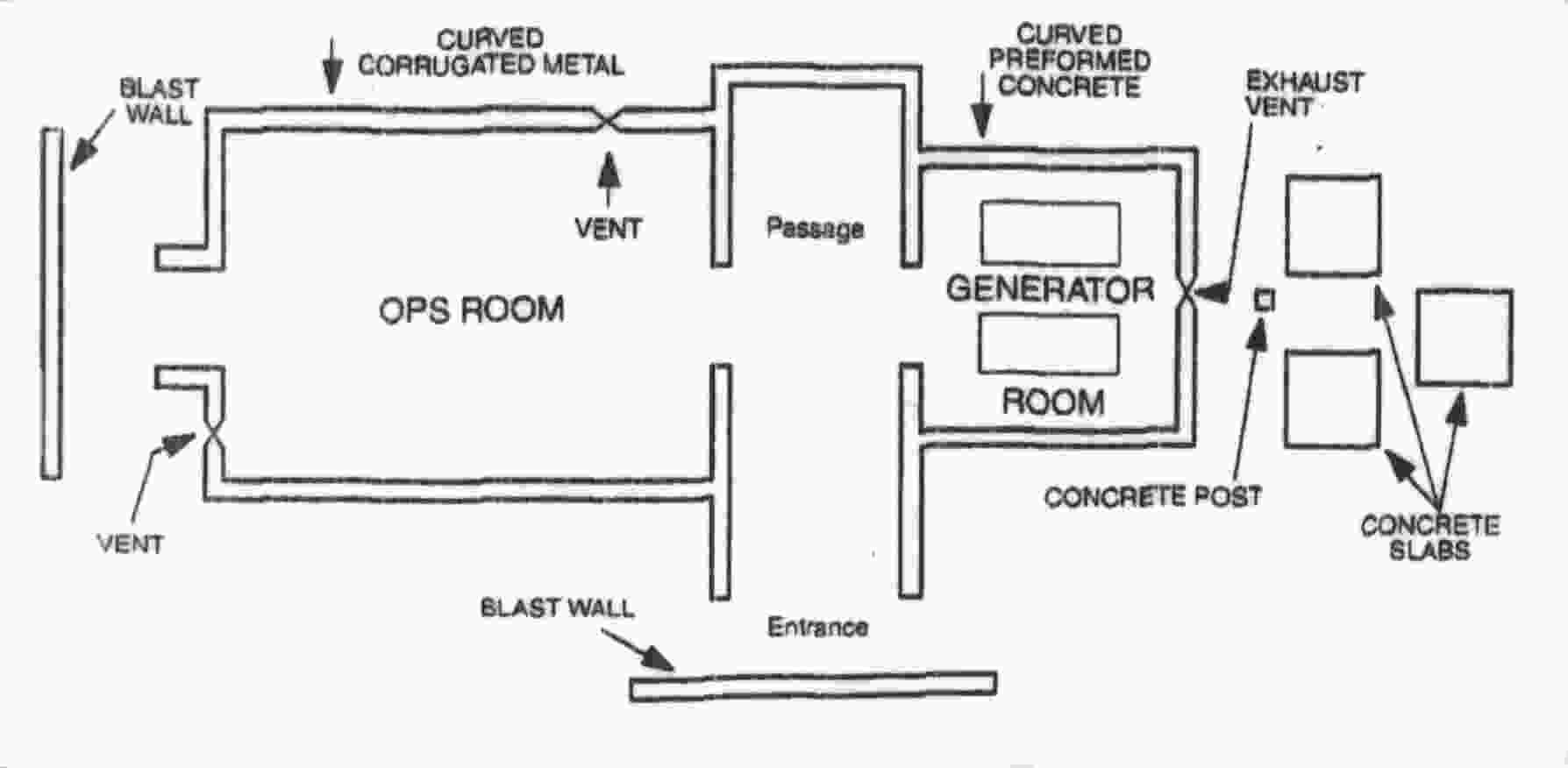

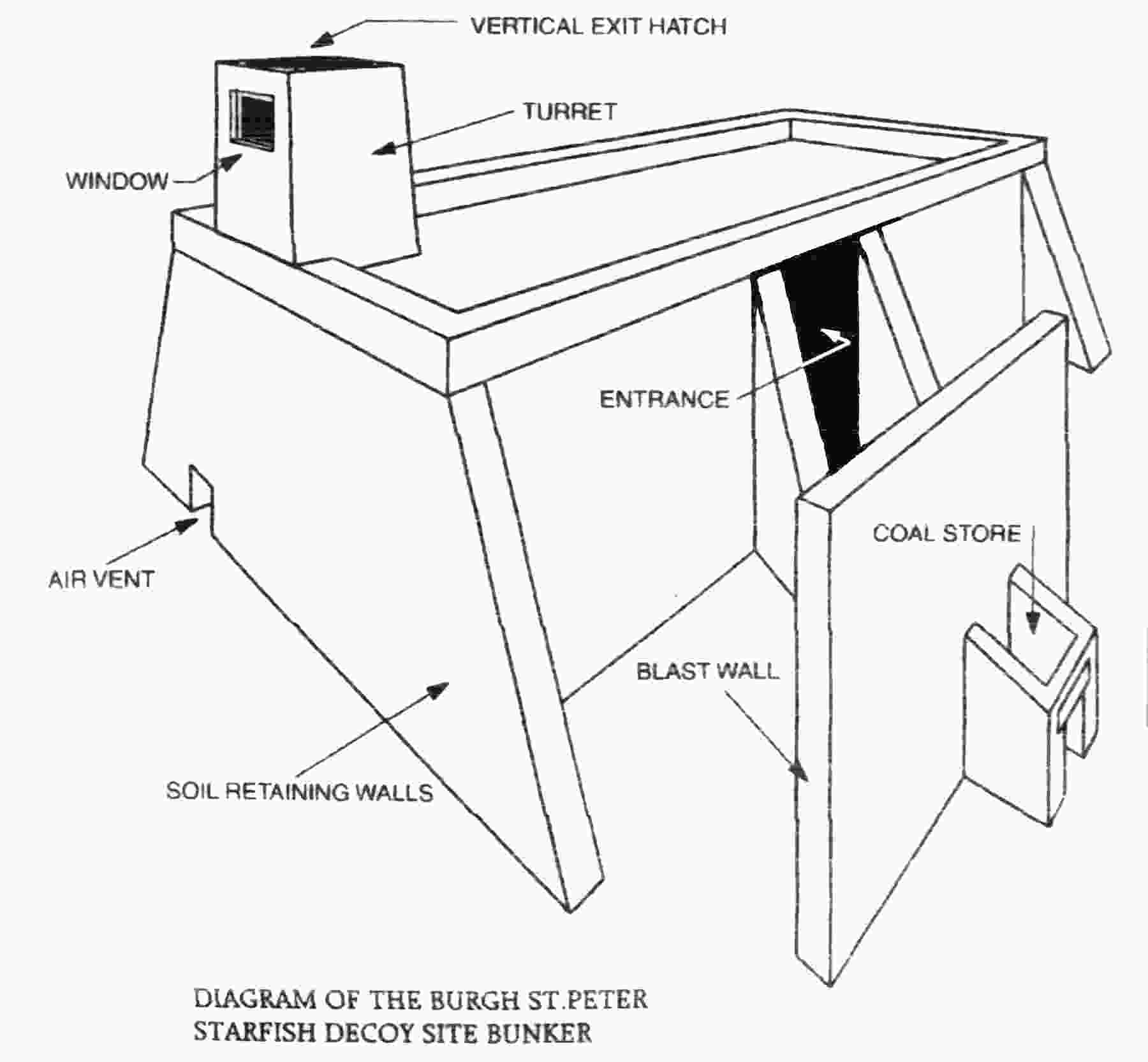

DECOY SITESWartime Deception in Norfolk and Suffolk by Huby FairheadAt the commencement of War World II, in 1939, the Air Ministry formed a secret department to oversee ways to fool the German Luftwaffe bombers by using decoys and other means of deception. Colonel Sir John Turner was placed in charge of British decoy and deception schemes. John Turner was born in 1881 and had been commissioned into the Corps of Royal Engineers in 1900. In 1931, following a long association with the RAF as a civil engineer, Turner became the Director of Works and Buildings at the Air Ministry in London. His knowledge as a qualified pilot, and of airfield construction and infrastructure made him a good candidate for the role of masterminding the creation of Decoy Sites when it arose. Colonel Turner’s Department, as it was known, had its headquarters at the Sound City Film Studios in Shepperton, Surrey. Owing to the British weather, most pre-war films were made under cover with the film sets being mock-ups and clever lighting made them look like the real thing. Because of their knowledge of “deception”, the film men became the backbone of Col. Turner’s Dept where they produced dummy aircraft and equipment, as well as going out to the selected sites to help set them up with local builders, farmers, and the crews who would man the sites. The crews also went to Shepperton (in most cases) on a two-week course to learn the trade of deception. The first Decoys seen locally were airfields - “K” Sites - for day use, set out on large fields, heath or warren land, and sometimes on disused WWI aerodromes. Props would include dummy aircraft of similar type to those used by the stations they were protecting. There would be mock bomb dumps and fuel stores, and the surface would be levelled to look like a landing ground. Impressed civilian aircraft, such as D H Moths, were employed on some sites to resemble Tiger Moth military training aircraft. Large sheets of canvas were painted and laid on the ground to represent hangars while, in some cases, old and disused vehicles were set around the site along with gun pits and camouflage nets. These dummy airfields looked very realistic from the air. The crews had their own buildings and trucks. Most “K” Sites were closed down in 1942/43 although a few were still in use in 1944. Even at ground level they could deceive. A young lad, out for a walk with family and friends in the Summer of 1940, spotted some Wellington bombers dispersed on an aerodrome near Thetford. For three hours they waited for one to start up and take-off. A few days later, his father came home laughing his head off and said “ We might well have waited for those planes to take off last Sunday – they were dummies!” Decoy Sites like this one at Snareshill were amongst the war’s best kept secrets, under cover of “Col. Turner’s Dept”. “Q” Sites, sometimes on the same site as a “K”, were for night use. From the air they would have looked like a runway flarepath and, for authenticity, had light patterns that included obstruction lights. These were red and placed on hangars and other tall buildings to stop our aircraft landing on them by mistake. Later, a bar of red lights was placed across the flarepath and could be seen when on approach. This was added after a number of our own aircraft had attempted to land, sometimes with fatal consequences. Some of the early dummy flarepaths were created using Gooseneck Flares. Remains of Fulmodeston "KQ" Decoy Airfield. Photo by Bill Green 1996. The “Q” Site crew had a powerful Chance Light (similar to a small searchlight) on top of their bunker, codenamed “Scarecrow”, and this could be used to simulate aircraft taking off, landing and taxiing. Power was provided by generators within the bunker. Bunkers were of similar design like a small Nissen hut, but each one appeared to differ. Some sites had a bunker above ground whereas on others it was below ground – some sites had both types. One end, covered by tin sheeting, was the Operations Room with the runway light controls and a telephone connected to the headquarters station - plus basic comforts such as a Tortoiseshell stove, table, etc. The other room housed the generator and was covered with steel sheeting or arched, pre-formed concrete - feed pipes ran to the generator from the fuel tank outside. Normally, there were two fifteen-inch ducts for air intake and one for the exhaust. Between the rooms there was a passageway that led outside, protected by a blast wall. There was another exit, sometimes vertical, from the Ops. Room. “Q” Sites were still being built for the RAF and USAAF in 1943/44, with the last ones closing down at the end of the war. Layout of a typical Decoy Airfield bunker. drawing by Doug Willies 1996. In order to draw the enemy bombers from our towns and cities, dummy towns known as Starfish Sites were set up on open land between one and eight miles from the intended target. In daylight, the equipment resembled chicken sheds, etc., but when ignited at night the boilers and fire baskets looked just like bombs exploding, incendiaries burning and buildings on fire – these effects could be made to last a number of hours. QL lights were added to Starfish Sites but, on their own sites, were designed so that at night they could look like factories, marshalling yards, shipyards, steelworks, etc. QL lights ingeniously included welding flashes, railway signals (red and green), red railway crossing gate lights, tram car electrical flashes, standard lamps. They could also be made to look like open skylights, doors and windows where someone carelessly had not complied with the Blackout regulations.

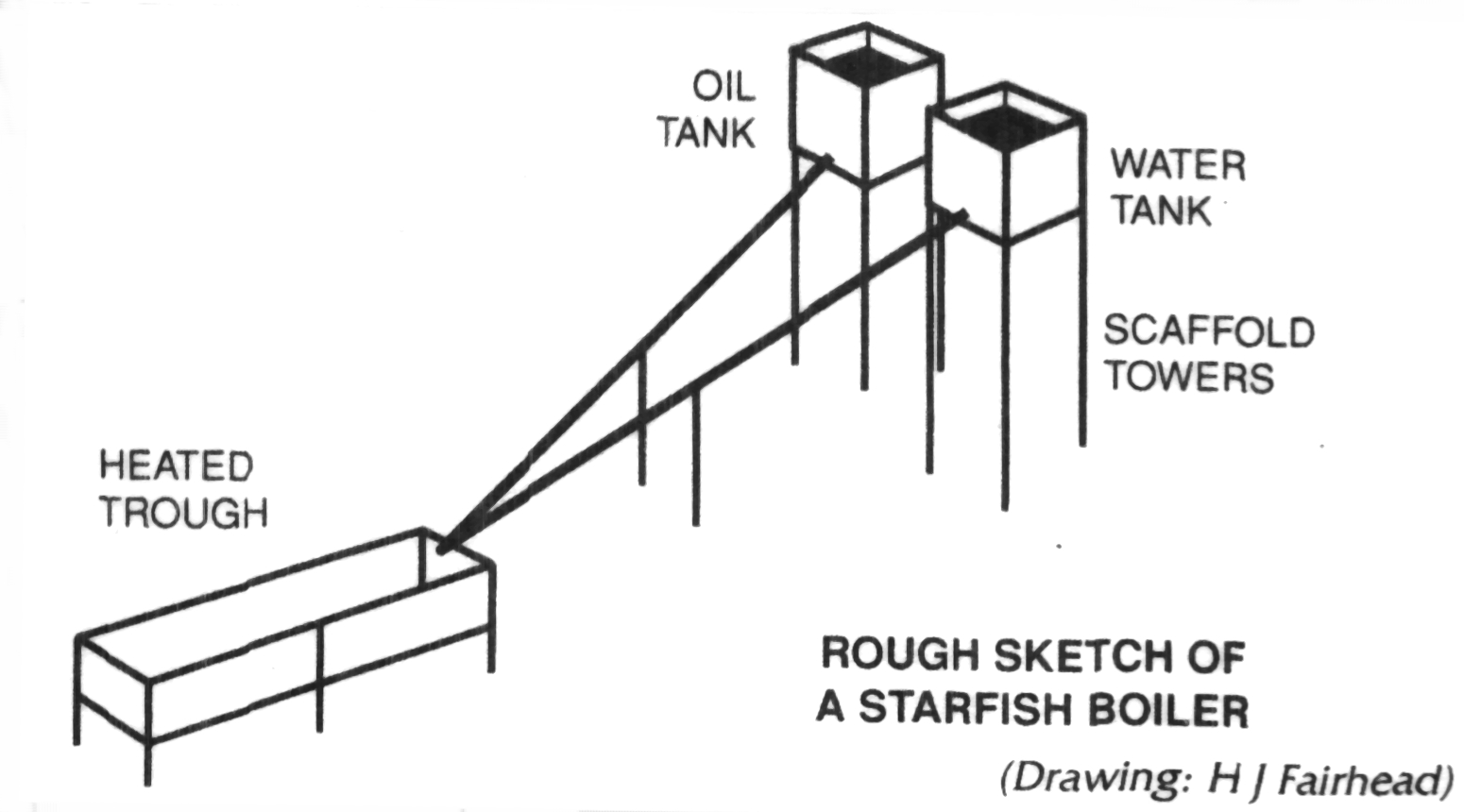

As a five-year old girl, Janet Zelnick used to visit her grandfather, a retired train driver – not in the front room of his cottage but in the control bunker of the top-secret, night-time Decoy site for the marshalling yards at March in Cambridgeshire. To the crews of German bombers, the decoy would have looked like the real target, with all the associated lights, standard lamps, signal lights – even the open fire box of a steam locomotive glowing in the dark. While Janet can remember all the details vividly, she finds it frustrating when other people cannot recall the Decoy loco site at Stags Holt. But Janet knows her grandad, William Frost, was an important and unsung hero, one of the almost forgotten band of men who, in serving with Col. Turner’s Dept., regularly risked their lives on the Home Front. Before World War II, Mr Ben Thompson worked for Rockland Reed and Rush Company at Rockland St Mary, Norfolk. There was a small factory near the New Inn Staithe, off Rockland Broad, with another factory the other side of the River Yare, at Buckenham - products such as mats were produced there. A few months after the start of WWII, the company was taken over by Sound City Films of Shepperton. Ben Thompson and the other employees, including Mr “Manny” Farrow, worked for the new company, making Fire Baskets and Wicks for Starfish decoy town sites. The baskets were box-shape wooden frames covered with wire netting and filled with creosote-soaked reed, rush and wood off-cuts. Sacking was fixed to the outside of the basket, with roofing felt over the top to keep the contents dry. The Wicks consisted of a tube of wire netting about one foot six inches long by six inches wide. They were filled with oil-soaked rags and wired up with an electrically-fired detonator to ignite boiler troughs. Boilers consisted of two large tanks on scaffolding, with pipes leading via toilet-type cisterns to a long trough. One tank was filled with oil, the other with water. Inside each trough was a Wick containing the electrically-fired detonator that would initially set light to the oil content. Once the oil was burning well, cisterns on the tanks would allow alternate flushes of oil and water to run into the trough, giving an explosion of fire - very much like someone putting out a large frying pan fire with water - flames reached over thirty feet into the air.

Fire baskets were set out in patterns over the site to take on the overall shape of buildings and the angle-iron framework of the base was about the size and shape of a coffee table. On top of this sat the wire-netting basket, plus “flare-cans” topped up with creosote placed inside. A flashbag (detonator) was positioned under the basket, wired to the firing sequence from the bunker. Once the basket was burning the flare-cans would catch fire and give off a different flame with smoke. When burning at night they would look just like flames coming from the windows and doors of a building with plenty of smoke. There would have been sufficient baskets to last several hours and they would have been replaced the following day by reserve baskets stored on site.

Ben recalled that, after several weeks of work, a stock of Boiler Wicks and Fire Baskets had built up so it was decided to deliver them to the sites, the nearest being at Bramerton. This one and another Starfish at Plumstead, were decoys for Norwich, and were manned by RAF personnel. Baskets and Wicks were also taken to a number of Royal Navy manned sites in Norfolk and Suffolk including: Burgh St Peter in Norfolk, about three miles west of Lowestoft, where the lorry was unloaded in a farmyard, possibly Hall Farm, Somerton, just west of the dunes and north of Winterton-on-Sea, Norfolk. Also Lound in Suffolk which was west of the A12, beside Jay Lane, about one mile from the coast between Lowestoft and Gorleston-on-Sea. These sites were decoys for the ports of Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft respectively. Three other naval Starfish sites were in Essex: one just north of Walton-on-the-Naze; another at Thorpe-le-Soken, about five miles north of Clacton-on-Sea, and the third at East Mersea on Mersea Island. These were decoys for the naval base at Harwich. In total, there were approximately 630 Decoy Sites in the United Kingdom. Of which, 230 were decoy airfields and 400 were decoy towns, marshalling yards steelworks, foundry and factory complexes. Figures given at the end of the war claimed a chain of 500 Decoy Sites and of these, the dummy airfields had been bombed 443 times, with the operational aerodromes being bombed 434 times. The decoy towns were bombed about 100 times, drawing some 5% of the bombs intended for towns and cities. Official figures declared that Decoy Sites saved an estimated 2,500 lives and avoided 3,000 injuries; four civilians were killed through raids on decoy sites. These 1946 figures seem to be on the low side. It should be noted that, in most case, only bombs dropped on sites could be counted as being “dropped on the decoy”. After the war, however, it was agreed that bombs dropped within two miles of a site should have been counted to allow for inaccuracies due to Anti-Aircraft fire, fighter aircraft, weather conditions or poor bomb-aiming and navigation. K: Decoy Airfield. Day-time use with dummy aircraft, vehicles, buildings, etc. Q: Decoy Airfield. Night-time use with dummy flarepath lights, obstruction lights, etc. QL: Night-time Decoy Town with various lights. Starfish: Night-time Decoy Town with various fires to simulate bomb hits. Other decoys included Coastal Gun Sites. Also, under Operation ‘Fortitude’ (D-Day deception) there were dummy tanks, lorries, landing craft; plus at night, the lights of dummy Army lorries heading towards the coast. In operating these sites, the Decoy Crews were inviting the Luftwaffe to bomb them instead of the real target and, consequently, put their own lives and the local villagers at great risk. Happily, this did not prevent close ties being formed with local people, for many of the men met their future wives within the community. Following many years researching the subject and locating the dwindling number of surviving Decoy Crew members, I have gathered sufficient material to publish two books and create a permanent archive and exhibition in the museum. These activities have ensured that the invaluable contribution made by the men of Colonel Turner’s Department will never be forgotten. Some images from our section on decoys. |

|||||||||||

|